Osho Rajneesh Excerpt

Table of Contents

1. From Tantra to Zen

2. The Early Years

3. "An Experiment to Provoke God"

4. The Rise and Fall of Sheela

5. Poona Revisited

6. "I Leave You My Dream"

7. Master of Provocation

Illustrations

Bibliography of Sources Cited

Preface

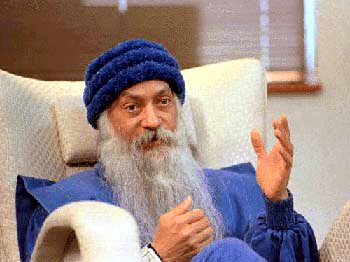

This book provides a brief introduction to the controversial guru

Osho Rajneesh, also known as Bhagwan. Reflecting some twenty years

of contact with his followers, it also draws upon his books and

those of his adherents, ex-members, and other academics and

commentators, as well as from a wealth of media, video, and internet

material.

Writing more than ten years after his death, I find it difficult

to predict if Osho left a lasting legacy or if his movement, like so

many others, will eventually disappear. Nevertheless, during his

lifetime his impact was dramatic.

My aim, in the space available, has been to convey an impression

of the man and his movement by representing a number of different

views of his life and teachings. One of the challenges of producing

such an account is dealing with the inconsistency that Osho often

displayed, leading to a wide range of interpretations. For this

reason, I have necessarily had to be selective.

Spiritual teachers sometimes change either their name or the name

of their movement to better fit the mood of the times. Osho,

likewise, adopted and shed a number of titles during his career. As

"Osho" was the last he assumed, I refer to him by this name for much

of the book. However, when describing historical events, I use the

name that was in usage at the time. This may be mildly confusing,

but I have thought it best to remain as consistent as possible to

the historical record.

My thanks to everyone who contributed to this book and especially

to those "lovers" of Osho who made it possible.

Top

1. From Tantra to Zen

Osho has been described as "the most dangerous man in the world,"

an "iconoclast," and a "great four-dimensional mystic." He was a man

who devoted a lifetime to challenging the systems, institutions, and

governments that he considered to be atrophied, corrupt, neurotic,

or anti-life. This chapter addresses his intellectual influences and

work.

His teachings were not static but changed in emphasis over time

and represent an enormous body of work that is impossible to cover

in full. In fact, he reveled in paradox and inconsistency, making it

difficult for a biographer to present more than a flavor of his

work. This is partly because, as he said, he taught neither ideology

nor anti-ideology but "a way of being, a different quality of

existence" (The True Sage, 125). It is also because "a perfect man

is never consistent. He has to be contradictory" (ibid., 126-27).

Notwithstanding these challenges, a number of themes are

particularly significant. It is also possible to trace the

development of his vision, especially in terms of his commentaries

on religious scriptures and his call for "a new man."

In examining his work, it should be remembered that his teachings

were not presented in a dry, academic setting. Instead, and

especially in the case of his earlier lectures, they were delivered

with an oratory which many found spellbinding. This was partly

because he was a genuinely gifted speaker – many say hypnotic – and

partly because he read widely and voraciously. His words appeared

erudite and informed but never as if he were simply passing on

secondhand information.

Having said this, some of his key Western inspirations include

Nietzsche, Krishnamurti, Freud, and Gurdjieff. Sympathy with the

philosophical position of Nietzsche may be detected in Osho's

crusade against religion. As an early biographer noted, there is not

much difference between Nietzsche's claim that "[o]ne should not be

deceived: great spirits are skeptics. Zarathustra is a skeptic ...

Convictions are prisons" and Osho's assertion that faith binds but

doubt frees and that it is therefore "necessary ... to inculcate

skepticism in place of blind faith" (Prasad, Rajneesh: The Mystic of

Feeling, 11).

It does not seem that Krishnamurti, one of Osho's famous

contemporaries, embraced much of Osho's mission. Yet, as with

Nietzsche, there are clear similarities between their

pronouncements. Both rejected orthodoxy as inauthentic, and Osho

would have agreed with Krishnamurti's view that religion can be

defined as "the cultivation of freedom in the search for truth"

(ibid., 43).

Osho made use of Freud's psychoanalytic language when he spoke of

the ego and of neurotic and patterned reactive behavior as the

result of the unconscious. Perhaps Osho's greatest debt to the

Viennese psychoanalyst may be discerned in his incorporation of

catharsis into his meditations, making them unique in contemporary

spiritual practice.

But of all his intellectual mentors, it was Gurdjieff of whom

Osho spoke most approvingly. For, like Gurdjieff, he taught that

human beings are reactive entities who do not know they lead a

mechanical existence. This is, according to Osho, because their

lives are rooted in the past, "moving in the same circle, in the

same rut" ("Morning Discourse," 25 Apr. 1977).

Osho's message was ultimately a positive one. He taught that we

are all Buddhas and that all have the capacity for enlightenment.

Every human being, according to Osho, is capable of experiencing

unconditional love and of responding rather than reacting to life.

As he said: "You are truth. You are love. You are bliss. You are

freedom" (The Goose Is Out, 286). It is possible, he suggested, to

experience innate divinity and to be conscious of "who we really

are." We do not do so only because our egos prevent us from enjoying

this experience: "When the ego is gone the whole individuality

arises in its crystal purity" (ibid., 142). The problem is how to

bypass the ego so that our innate being can flower; how to move from

the periphery to the center. Osho's answer came from a variety of

viewpoints.

His first tactic was to identify the ways in which the ego, or

mind, comes to exert its control. This occurs, he said, because the

mind is first and foremost a mechanism for survival. At some

unspecified point in our early development, we found it "necessary

to stop being ourselves" (Belfrage, Flowers of Emptiness, 28). The

mind replicates behavioral strategies that, in the past, proved

successful in ensuring survival. But in appealing to the past, the

mind prevents us from living authentically in the present. Worse

still, this strategy means that we continually repress what we

genuinely feel on the grounds that it may topple the fragile

machinations of the mind regarding what we think we ought to feel.

In so doing, we automatically close ourselves off from experiencing

the joy that naturally comes when we move into the present because

"the mind has no inherent capacity for joy. ... It only thinks about

joy" (The Goose Is Out, 13). The result, he warned, is that we

unconsciously poison ourselves with various neuroses, jealousies,

fears, etc. (see Bharti, Death Comes Dancing, 11), accumulating

false religious teachings instead of living in joyous, authentic

awareness.

This kind of unconscious behavior does not produce the effect we

desire. For instance, by repressing sexual feelings, we hope to

pretend they do not exist. Repression only leads to the re-emergence

of these feelings in another guise to haunt our lives. The result,

he said, is that society is obsessed with sex, evidence for this

being the high incidence of rape, prostitution, and pornography (see

The Secret of Secrets, 2:344). The solution that he proposed was

simple. Instead of repressing, we should accept everything – our

thoughts, feelings, prejudices, and opinions unconditionally: "Be

total. Be authentic; be true" (Roots and Wings, 111). In short: "We

have been repressing anger, greed, sex ... And that's why every

human being is stinking. ... Let it become manure, ... and you will

have great flowers blossoming in you" (Be Silent and Know, 36). This

solution could not be intellectually understood, as the mind would

only assimilate it as one more piece of baggage. He offered a

practical answer: meditation.

According to Osho, meditation is not simply a practice. It is a

state of awareness that can be realized in every moment. What he

presented to his followers, then, was a series of techniques to

implement this approach. As we will see, he incorporated the use of

Western psychotherapy as a means of preparing for meditation – a way

for his disciples to become aware of their mental and emotional

refuse. He also introduced his own, original techniques,

characterized by moments of alternating activity and silence. In

all, he suggested over a hundred techniques for successful

meditation.

The most famous remains his first: Dynamic Meditation. This is

divided into five stages. In the first, a person engages in ten

minutes of rapid breathing through the nose. The second ten minutes

are dedicated to catharsis: "[L]et whatever is happening happen. ...

Laugh, shout, scream, jump, shake--whatever you feel to do, do it!"

(Meditation: The Art of Ecstasy, 233). In the third stage, the

person jumps up and down shouting hoo-hoo-hoo. In the fourth stage,

everything stops. As one disciple said of this stage: "I was too

tired to think, too drained from the catharsis ... [M]y body was too

tired to fidget, to move; it was utterly relaxed" (Bharti, Death

Comes Dancing, 18-19). Finally, the exercise is completed with

between ten and fifteen minutes of dancing and celebration.

Not all of Osho's meditation techniques are as animated, although

many are. In his Kundalini Meditation, for instance, participants

are urged to shake for the first fifteen minutes until they "became"

the shaking. In contrast, others, such as the Nadhabrahma Humming

Meditation, are much gentler, although they also contain some

movement and activity. His final formal meditation technique is

called the Mystic Rose. It combines lengthy periods of intense

activity with equally lengthy periods of rest-- three hours of

laughing every day for the first week, followed by three hours of

weeping each day for the second. The third week entails silent

meditation. The result of these processes is the experience of

"witnessing" wherein "the jump into awareness becomes possible"

(Meditation: The Art of Ecstasy, 116).

Osho put other devices into place to propel his disciples into

conscious awareness. One was simply for him to function as a master

and to be authentically present with his followers: "A Master shares

His being with you, not his philosophy. ... He never does anything

to the disciple" (The Rajneesh Bible, 419). He also delighted in

being paradoxical and in surprising his audiences with behavior that

seemed to be entirely at odds with traditional images of enlightened

individuals. He explained that all such behavior, however capricious

and difficult to accept, was "a technique for transformation" to

push people "beyond the mind." Another device was the initiation he

offered his followers: "[I] f your being can communicate with me, it

becomes a communion. ... It is the highest form of communication

possible: a transmission without words. Our beings merge. This is

possible only if you become a disciple" (Bharti, Death Comes

Dancing, 104). Yet ultimately, Osho said, anything and everything

was an opportunity for meditation.

Through such devices, Osho hoped to create "a new man" who

combined the spirituality of Gautama Buddha with the zest for life

embodied by Zorba the Greek from the novel by Nikos Kazantzakis: "He

should be as accurate and objective as a scientist ... as sensitive,

as full of heart, as a poet ... be [as] rooted deep down in his

being as the mystic" (Philosophia Perennis, 10). The "new man," he

continued, should reject neither science nor spirituality but should

embrace them both to create a new era. He considered humanity to be

threatened with extinction due to over-population, impending nuclear

holocaust, and diseases such as AIDS, and he believed that many of

society's ills could be remedied by scientific means. Neither would

the "new man" be trapped in institutions such as family, marriage,

political ideologies, or religions (see ibid., 23). His term, "the

new man," embraced men and women equally, whose roles he saw as

complementary (see Palmer, Moon Sisters, Krishna Mothers, Rajneesh

Lovers). Indeed, he put women into most of his movement's leadership

positions.

During his life, Osho delivered eloquent commentaries on all of

the major spiritual traditions, including Taoism, Christianity,

Buddhism, Yoga, and the teachings of a variety of mystics, and on

such sacred scriptures as the Upanishads. But towards the end, he

came to be described as a Zen master. An early biographer observed

that his closest philosophical links were not with Zen but with

practitioners of Tantra, who regard the body as an essential aspect

of spirituality (see Prasad, Rajneesh: The Mystic of Feeling,

141-42). In fact, Osho rejected the suppression of emotions,

emphasized the positive benefits of spontaneity and naturalness, and

conceptualized everything as being in dynamic polarity with its

opposite, maintaining that both polarities should be accepted. His

early lectures often focused on traditional Tantric themes such as

the existence of spiritual centers in the body called chakras.

Nevertheless, the majority of his publications, from early on,

focused on Zen. As time went on, the communes which arose around him

tended to reflect "the aesthetic of Zen" in their beautiful

environment. But in terms of his corpus of teachings, to try to fit

him neatly into any single category, either as a "Zen master" or a

"Tantric guru," is to do him a disservice.

As might be expected, due to his message of sexual, emotional,

spiritual, and institutional liberation, and his contrariness, his

life was surrounded by conjecture, rumor, and controversy. Was he

enlightened or, as critics suggested, an indulgent charlatan? This

will be addressed at the end of this book. First, I will trace the

events of his life as a prelude for further discussion.

Top

2. The Early Years

Over 700 years ago, it is said, a holy man, after many lifetimes

of searching, stood on the brink of enlightenment. At the end of a

twenty-one-day fast, and three days before he was due to achieve

this state, he was killed. As a result, he had to return to the

earth one last time to complete this enterprise. Thus, Mohan Chandra

Rajneesh was born into a Jain family in Kuchwada, India, on 11

December 1931, the son of a cloth merchant and one of eleven

children. He was brought up by his maternal grandparents and was

soon recognized to be a natural leader among local children. He was

bright, gifted at art and storytelling, and rebellious, and often

played truant in order to swim and play with his friends and

childhood sweetheart, Shashi. Later, he experimented with hypnotism

and was associated for a brief period with communism, socialism, and

two nationalist movements, the Indian National Army and Rashtriya

Swayamsavek Singh. During this time, he acquired a reputation as an

egotistical, immodest, discourteous, even seditious young man (see

Joshi, The Awakened One, 27). It was a reputation he would never

outgrow.

Death was present in young Rajneesh's life. His grandfather, whom

he adored, died when he was seven; his sweetheart and cousin,

Shashi, died of typhoid when he was fifteen. At nineteen, he

enrolled as a student at Jabalpur University, earned a master's

degree at the University of Sagar, and went on to teach philosophy

at Raipur Sanskrit College. It was at Jabalpur in March 1953, at age

twenty-one, that he had an extraordinary experience during which he

felt "as if I was going mad with blissfulness" (in Brecher, A

Passage to America, 29). After months of lassitude during which he

said he fought to maintain his sanity, he suddenly felt filled with

a new energy: "I have known many other deaths, but they were nothing

compared to it. They were partial deaths. ... That night the death

was total. It was a date with God and death simultaneously" (ibid.,

29). He had, he would explain later, achieved the enlightenment he

had so narrowly missed in his previous life.

Such an experience is often characterized as ineffable, and

Rajneesh too apparently told no one of his enlightenment until years

later. By the mid-1960s, he had become increasingly dissatisfied

with conditions in India and began to hold public meetings. These

quickly reinforced his reputation for controversy but proved so

popular that he was able to devote himself full time to touring. As

he questioned India's institutions and practices, he became well

known for his reluctance to shy away from argument: "With or without

reason I was creating controversies and making criticisms. I began

to criticize Gandhiji, I began to criticize socialism" (in Joshi,

The Awakened One, 80). Both, he said, glorified poverty when it

should be rejected. He condemned brahminical religion as sterile and

proclaimed all religious and political systems to be false and

hypocritical (see ibid., 88). His response to the crisis he outlined

was to hold meditation camps that would involve catharsis and

activity to bring about what he described as "authentic religiosity.

For the most part, these early meditation camps and public

speeches, conducted in Hindi, attracted few Westerners. In a book

written in 1970, a devotee described the attraction he and other

Indians felt: "[T]he roles he plays are dramatic and the impact he

makes on all who come near him is staggering ... [T]here is

something really powerful and extraordinary about him. His

indomitable personality never fails to exert a strange fascination,

even over people who do not agree with his views" (Prasad, Rajneesh:

The Mystic of Feeling, 1). By 1970, a small circle of Indian

followers had grown up around him. Consistent with his own teaching,

Rajneesh initially resisted the idea of setting up a formal

organization, but was ultimately persuaded. Reportedly, the first

formally initiated disciple, Laxmi, immediately recognized Rajneesh

as her spiritual teacher when she went to meet him one day in Bombay

with other devotees. She wore orange, having felt drawn to the

color. He called her to him with these words: "This is beautiful.

This is the way existence wants it to happen. Today, my neo-sannyas

begins" (Brecher, A Passage to America, 33).

After this experience, Rajneesh began to regularly initiate

individuals, especially those who participated in his meditation

camps, into "neo-sannyas." This, he explained, was inspired by

traditional Indian renunciation, but was to be a new and celebratory

form centering on "the death of all that you were yesterday" (A Cup

of Tea Pune, 85). Such renunciation involved the surrender of

everything that prevented the individual from living totally in the

present. The important aspect of the process, said Rajneesh, was not

surrendering to him but surrender itself: "[T]he real thing is not

to whom you surrender. The real thing is the surrendering"

(Meditation: The Art of Ecstasy, 108). As one biographer described

it: "To be initiated into sannyas means that you have come to

realize that you are just a seed, a potentiality. It's a decision to

grow, a decision to drop all your securities and live in insecurity.

You are ready to take a jump into the unknown, the uncharted, the

mysterious" (Bharti, Death Comes Dancing, 23). Each new sannyasin

was given a new name and a mala, a necklace of 108 beads with

Rajneesh's photograph on it. They were required to wear orange

clothes as well. One follower observed wryly: "Orange put you on the

spot. Suddenly you had to stand up for yourself. Suddenly you had to

walk your talk. 'A sense of humour' [Rajneesh] observed 'should be

the foundation stone of the future religiousness of man.' Well, the

first time you wore your orange to the supermarket you found out

exactly what that meant" (Sam, Life of Osho, 258.

In 1970 Rajneesh decided to stop traveling and settled in Bombay

where he continued to give regular public lectures. By the following

year, he had begun to attract a small Western following, and these

early Westerners enjoyed personal and close relationships with their

master. Among their number was a shy twenty-two-year-old English

woman named Christine Wolff who was at first horrified by her

encounter with Rajneesh and his meditation camps. Shortly

afterwards, we are told, Rajneesh advised her to take sannyas and

gave her three days to deliberate the matter. Early the next

morning, she woke up and knew that she had to become initiated.

Soon, past-life memories came to her and she realized that she had

been Shashi, his childhood sweetheart who had promised on her

deathbed to return to him. Taking on the name Ma Yoga Vivek, she

became his constant companion and the focus of much speculation.

What, one of his followers later asked him, did he do with Vivek? "I

am killing her slowly," replied Rajneesh in a public lecture. "That

is the only way for her to get a totally new being, to be reborn"

(Bharti, Death Comes Dancing, 117).

Another notable occurrence in 1971 was that Rajneesh changed his

title. Before, he had most commonly been addressed as "Acharya," a

term of respect meaning teacher. Now, he said, the appellation

"Bhagwan" was more appropriate. The new name has been variously

translated by sannyasins as "the Blessed One" and "Self-Realized."

Bhagwan's appropriation of the title offended many Indians: "[W]

hile turning to God was highly acceptable to a conventional world,

turning into God wasn't" (Brecher, A Passage to America, 15).

Bhagwan himself was unconcerned about the controversy. Typically, he

appeared to relish it: "Only those who are ready to dissolve with me

remain. All others escaped." Subsequently, he continued, "The crowds

disappeared. The word 'Bhagwan' functioned like an atomic explosion"

(The Discipline of Transcendence, 2:107). The change had another

function: it mirrored a new focus for his attention. Less and less

was he interested in giving lectures to the general public. Instead,

he said, his new goal was to transform those individuals who had

committed themselves to sannyas through an inner communion: "Now I

give you being, not knowledge. I am going to give you knowing - and

that is totally different" (ibid., 107).

Soon, Bhagwan began to alternate between delivering lectures in

Hindi and English as the number of Westerners started to swell. Said

one later: "The melody of his words captured my enthusiasm and

imagination. He was asking me to dance with him, and he said it in

words of love. It all made total sense" (Milne, Bhagwan: The God

that Failed, 43). Many of these early followers were sent to a farm

commune located in nearby Kailash and understood that they were to

establish the foundations of a permanent community: "The entire

focus was on work with the spirit of surrender. People did react to

the conditions strongly, but they also learn[ed] how to live in a

commune in love and acceptance" (Joshi, The Awakened One, 119).

After some of the workers fell ill, the farm was closed. Bhagwan was

not well either. In particular, his asthma was exacerbated by the

Bombay air and his diabetes began to worsen alarmingly. It was felt

that a move to a more congenial location was necessary. Laxmi was

sent to find a suitable place that could enable Bhagwan to recover

and would accommodate the burgeoning numbers of people who wanted to

visit. Accordingly, six acres in one of the more prestigious suburbs

of Poona (also known as Pune) were purchased early in 1974. Money

for this undertaking was donated by sannyasins and well-wishers. A

new experiment, on a larger scale, was about to begin.

Top

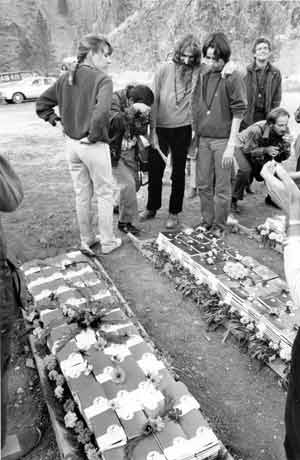

Illustrations

AP/WIDE WORLD PHOTOS |

AP/WIDE WORLD PHOTOS |

AP/WIDE WORLD PHOTOS |